Media, politics, and ideology may play a massive role in making things visible or invisible. When is an individual's personality made visible, and when and how can she be deliberately made invisible? Faces and portraits are two very distinguished things. The portrait is a reproduction of the face, while the face is the point of access to a person's character. Portraits may represent a character's traits, yet they do not grant direct access to the depicted person in real; they are products of intentions and interpretations.

The starting point for the project Faces was this archival photograph showing a group of South Africans, exotically dressed up and gathered in a way that one could not discern the individuality of each person. The image emphasized the factor of a group—instead of individuals—and the aura of savageness. Later we found that the collective was to feature as the main attraction of the Savage South Africa spectacle at the Greater Britain Exhibition at Earls Court in 1900.

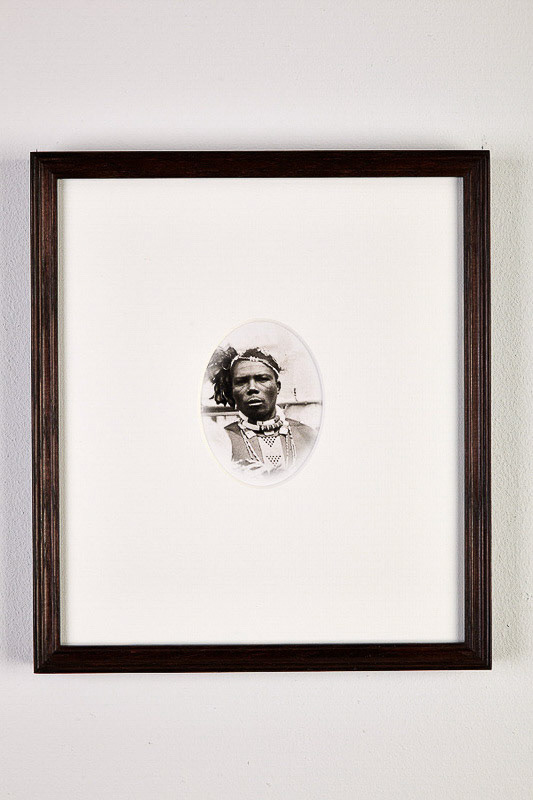

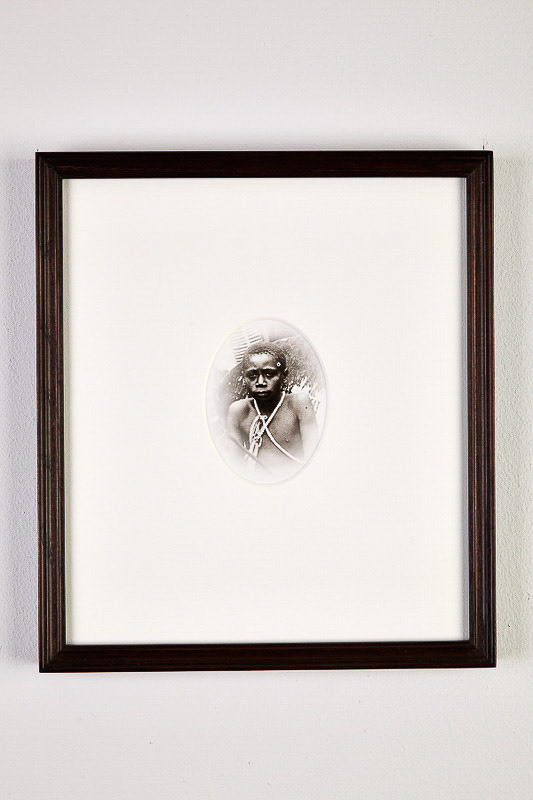

We were thinking of turning around this situation of representation. In the early days of commercial photography, around 1900, it was still costly to develop a negative plate. Instead of taking expensive individual portraits, it was custom to take photographs of the whole family on a single plate, which could later be exposed multiple times, to grant every family member a personal portrait cut out of the group image. We treated the archival photograph like a family picture and rendered individual portraits from each person of the group. It was a method to reframe each character's individuality, a process that later turned out to reveal some truth about the history of the original photograph.

In the archives of the KwaZulu-Natal University in South Africa is an old photograph which was described as ‘Chief of Zulu, His Wives and a troop of Zulus’, showing a group of men and a few women. They were martially decorated and carrying shields and spears. Yet, something was odd about this image. Some of the warriors even seemed to look seasick. What brought these men and women to dress like this and pose for a group picture? Where had the photograph been taken? The background of the image shows pillars that seem unusual for buildings. They rather look like masts on a boat. The image was subtitled: 'Frank Fillis’ Savage South Africa’.

The photograph got our attention and we wanted to find out more. A newspaper article in the Westminster Budget from April 28, 1899, seems to be another piece in this puzzle. The reporter went to Southampton to attend the landing of the Union intermediate steamer The Goth. He was astonished, “seldom the deck or hold of a vessel carried such a motley cargo”, “black folks … and wild beasts”. Then he buttonholed Frank Fillis, “the Barnum of the Dark Continent”, who explained that you couldn’t expect to pick up rarities like these seven days a week. The black folks wouldn’t leave their home too readily, he had to hunt for them and some that he had got were worth their weight in gold. The value of the collection? Even though values of rarities in a showman’s business are priceless, Fillis estimates that £50,000 has been sunk into this collection of ‘Savage Africa’. The collection of valuable trophies would then have been brought to the Earls Court exhibition centre in London where they dwelled in the ‘native village’ that was being constructed there, to reflect “exactly what life is like on the borders of civilization in West Africa”.

Arranged scene taken on the streamliner The Goth as PR material to advertise the spectacle at Earl's Court in 1899.

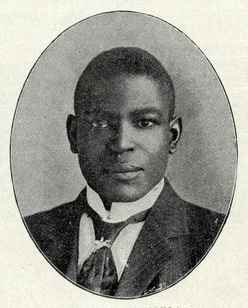

Peter Lobengula around 1905 in London.

Arranged scene at Earl's Court to advertise the spectacle "Savage South Africa"

The ‘Kaffir Kraal’ was one of the main attractions of the Greater Britain exhibition at Earls Court. Responsible for the whole exhibition was Imre Kiralfy, the first tenant of the Tower House, and Frank Fillis was a kind of sub-contractor who brought the South Africans to London. He was mainly res-ponsible for an equestrian spectacle re-enacting mythical episodes of the Zulu Wars at the Empress theatre. However, the financier of these shows was neither the colonial government in Cape Colony, nor Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Both had been vigorously opposed to such spectacles, arguing that they could not possibly give the European public an appropriate understanding of South Africa. The patron behind it was Cecil Rhodes, head of the Chartered Company and, at the time, the most powerful gold miner of the Greater British Empire.

The Savage South Africa show was all in his interest. His reputation in London was heavily damaged. A few years before, he had made deals with the Matabele King Lobengula who granted him the right to dig for gold in the land of the Mashona. The land had everything that humans needed for subsistence, yet it was poor in mineral wealth. His next target was the land of the Matabele. He pushed the agreement with Lobengula to the edge and armed the Mashona to fight against their alleged oppressors, the Matabele, until he finally invaded the Matabele land with a band of gunmen and machine guns.

Slides from "Faces, 2014". First shown at a festival for silent projection "If These Walls Could Talk" in Karachi in 2020.

This marked the outbreak of the Zulu Wars in the 1890s, with many casualties and assassinations of pioneer farmers. While Rhodes did not exactly start the war himself, he did everything to end the peace that preceded it, of which the colonial secretary in London was well aware. Rhodes’ plan to rehabilitate his name in Europe was to show the public how dangerous the savage South African people were. Imre Kiralfy gave him the opportunity for this propaganda campaign and Frank Fillis delivered the spectacle.